Our Verdict

Total War: Pharaoh’s battles may be limited by history, but Creative Assembly compensates for this with a complex, thematic, and highly dynamic campaign.

PC Gamer's got your back

What is it? A grand historical strategy game in the classic Total War style, set in Ancient Egypt.

Release date October 11, 2023

Expect to pay £50 / $60

Developer Creative Assembly

Publisher SEGA

Reviewed on AMD Ryzen 5 3600, Nvidia 2080 Super, 32 GB RAM

Steam Deck Unsupported

Link Official site

Total War: Pharaoh isn’t the best Total War game, but it is possibly the one I’m most impressed by. Creative Assembly’s chosen setting sits right on the precipice of military history. The Battle of Kadesh, which took place about 100 years before Total War: Pharaoh begins, is the earliest pitched battle that we have records of tactics and formations for. The most technologically advanced weapon of the time was the chariot. Cavalry didn’t exist, because the saddle hadn’t been invented yet.

Compared to the military engine that powered Rome, or the wild armies of Total War: Warhammer, Pharaoh has precious few tools to create an entertaining simulation of warfare. And yet, Pharaoh is a deeply compelling strategy game. Although its battles are almost Shogun-like in their simplicity, the campaign is anything but, offering a fiercely challenging scramble for power over an empire that is falling apart at the seams.

Pharaoh takes place shortly after Ramesses II has begun the long journey to becoming two vast and trunkless legs of stone, and the power gap that opened after his unprecedented reign. Playing as either an Egyptian, Canaanite, or Hittite general, your goal is to conquer enough of the land around the Eastern Mediterranean so that your name is forever carved into the stele of history.

In this, becoming Pharoah is merely the start of your aspirations, rather than the end goal. Around turn twelve of the campaign, you unlock a new system known as “Power of the Crown”. This lets you choose to follow the path of becoming either the Egyptian Pharaoh or the Great King of Hatti. These positions come with slightly different benefits, but they’re attained in the same way – winning a civil war.

Unlike the original Rome, in which the civil war was deployed as a narrative third-act twist, civil wars in Pharaoh are more systemic and can happen at any time. You can start them yourself, or they might be triggered by an AI faction, whereupon you can choose whether to participate. If you do, your name is added to a league table of pretenders. From there, you have a set number of turns to reach the top by earning as much Legitimacy as possible. Legitimacy is a resource that defines your ruler’s powers. It can be earned by winning battles, conquering lands that are sacred to your faction, constructing certain buildings and monuments, and engaging in a bit of courtly intrigue (more on this shortly).

You might become Pharaoh early on, but then you’ll need to maintain that position, fighting off other pretenders to your throne.

The impact this system has is significant. For starters, it makes Total War’s early game more immediately engaging, as you can have a crack at becoming Pharaoh as soon as turn 12. It also means progression isn’t necessarily a gradual, one-way accrual of power. You might become Pharaoh early on, but then you’ll need to maintain that position, fighting off other pretenders to your throne. You might get usurped, then have to claim the throne back. It just opens up more potential for emergent stories on the campaign map.

Even if you’re way off becoming Pharaoh, you can still wield power in a more limited fashion. The Pharaoh holds a court with several illustrious positions, such as Viceroy of Kush, Grand Vizier (spymaster), and First Commander. Each of these positions comes with its own benefits. The viceroy, for example, gets an annual salary paid in gold, while the Vizier can assassinate other court members. You can curry favour with the present holders of these positions to make use of their powers, or you conspire to take advantage of them in other ways, blackmailing them for additional favours, discrediting them to damage their legitimacy, or forcing them to vacate their position entirely, perhaps so you can assume it yourself.

This system is nothing like as involved as Crusader Kings’ elaborate political simulation, playing out more like a minigame that refreshes itself every in-game year. But it is fun to noodle around with, and can tie into the broader game in some interesting ways. If you’re in a civil war, for example, then successfully discrediting a rival might help you leapfrog them up the league table, damaging their Legitimacy while adding to your own.

Ten plagues

Should you succeed in becoming Pharaoh, your problems will be far from over, as you’ll inherit an empire at the end of its golden age. Things aren’t too bad at the game’s outset, which is good because you’ll be busy acquainting yourself with Pharaoh’s surprisingly complex economy system. There are five resources in the game: food, wood, stone, bronze, and gold. Food and bronze are crucial for maintaining armies, wood and stone for constructing buildings, while gold plays a role in pretty much everything.

Simply getting hold of all these resources can be tricky. Gold and bronze deposits are scarce on the map, while stone has a hard limit on how much you can mine across the entire game. This makes trading and bartering more vital than in any other Total War. But it gets harder as the game goes on, because soon enough your empire will start to collapse. The sanctity of Egypt and Hatti is founded upon numerous institutional structures named Cult Centres, and as civil war begins to damage those centres, the game world will descend into crisis. At this point, the colour palette of the map visibly changes, and you’ll start to be harassed by invaders from across the Mediterranean. Not just one or two boats either. Entire fleets will cruise down the arteries of the Nile delta, striking at both the head and heart of Egypt. These raiders cause more destruction, further destabilising the foundations of civilisation.

Fighting these different fires, all while trying to forge a legacy of your own, is a formidable challenge. Simply maintaining a decent sized army requires you to solve a whole bunch of logistical problems. Luckily, you can often mitigate some of the upkeep cost by building different kinds of outposts. These are subsidiary buildings that orbit your main city, ranging from temples that increase your favour with the gods, to forts where you can garrison your forces at a discount. Alongside the passive bonuses outposts provide, armies can also interact with them for temporary boons, like higher morale, greater movement range, or cheaper upkeep for a few turns. Indeed, planning your outposts carefully can yield substantial rewards, letting your armies cross vast swathes of the map, and making them cheaper and stronger in the process.

Chariots of fire

Zoom in on the action, and you can even hear the crude maces of Egyptian chargers thudding into the skulls of their enemies.

In short, Creative Assembly has built a sumptuous, diverse and thematic campaign. There’s a whole bunch of other stuff I haven’t mentioned, like how praying to different gods can provide different bonuses, and the victory condition-like Ancient Legacies that can spur you on your way to victory. But we should probably spend some time discussing the battles, as this is where Pharaoh’s weakspot lies.

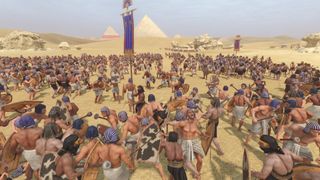

To be clear, Pharaoh’s battles are not bad. They are classic Total War affairs that combine robust tactical foundations with brutal physicality. Walls of infantry crashing into one another, arrow hailstorms thudding into the sand, chariot charges sending footsoldiers flying. Zoom in on the action, and you can even hear the crude maces of Egyptian chargers thudding into the skulls of their enemies. And of course, your battles are taking place beneath the shadows of pyramids that are already ancient, which is cool in its own right.

Pharaoh also does what it can to add some new ideas into the mix. Weather conditions are more diverse and dynamic. Being largely a desert country, Egypt’s weather is less rain and fog, and more sweltering heat and choking dust storms. These can be used to your advantage in some interesting ways. In one defensive battle where I was outnumbered, I positioned my army as deep into the desert as I could, high up on the scorching dunes. By the time the enemy reached me, their troops were exhausted from the heat, and I was able to mop up their ragged lines with minimal effort, turning a potential defeat into an easy victory.

Prince of Egypt

Ultimately though, there is only so much Creative Assembly can do to spice up the ranks of such an ancient civilisation. There are many faction-specific types of swordsmen, axemen, spearmen, chariots etc. But units are all slight variations on these categories. After controlling the wildly imaginative factions of Warhammer, and the pseudo-magical armies of Three Kingdoms, going back to slings and arrows is inevitably a bit deflating, especially when the contrast is as harsh as this.

There isn’t a whole lot Creative Assembly can do about this without throwing history out of the window. But there are some other issues that nag at the game. Getting a decent foothold in Pharaoh’s campaign is tricky. This is partly because there are so many different systems to account for, including ones I haven’t mentioned like attrition, which will decimate your forces if they stray off the road in desert environments. But also, defending cities have even more advantages than they did in earlier Total War games. On top of the city garrison and whatever army might be inside, they can also call in reinforcements from any satellite outpost garrisons. This means you may have to besiege the outpost before you can besiege the city, which is arduous. I reloaded my early game numerous times, as I just kept being rebuffed at every turn.

The other issue is that the game’s generals are sorely lacking in character. In its broader strokes, Pharaoh is wonderfully evocative of its era. The campaign map is beautifully detailed (and surprisingly diverse), while the entire game is steeped in the culture and traditions of ancient Egypt. But the game’s central belligerents are dead behind the eyes. They have none of the personality of Three Kingdoms’ colourful generals, dampening the drama created by civil wars and courtly plots.

All things considered though, Total War: Pharaoh is a success. This is a much harder setting to make work in Total War’s context than more familiar locales like Rome or feudal Japan. The battles may be the simplest they’ve been in a long time, but they still have that Total War magic, and Creative Assembly has built an evocative and exciting campaign around them.

Total War: Pharaoh’s battles may be limited by history, but Creative Assembly compensates for this with a complex, thematic, and highly dynamic campaign.